As a college writing professor and mindfulness practitioner who now studies Marriage and Family Therapy, I enjoy observing the intersections between the act of writing and its uses in the therapy room and beyond. Consider all of the ways you might have used writing to work through challenges in your personal or professional life: relationship conflicts, stress management, mental illness (anxiety, depression, etc.), self-esteem or self-confidence limitations, grief and loss, etc. Writing has incredible benefits for the body and mind. In this first part, I will discuss the cognitive benefits.

Writing Defined

Before I dive deeper into the cognitive benefits of writing, I think it’s important to define “writing,” and in what I am about to share, it can be described rather broadly in terms of form and function: handwriting, typing, a list, a freewrite (writing without stopping to generate ideas), a letter or email, wedding vows, a cover letter in your job application, a note left behind for your roommate, an old family story, explaining a concept, texting a friend, signing your name, etc. For as many reasons as we write, there are as many benefits for the health and wellbeing of our brains.

Where in the brain does writing happen?

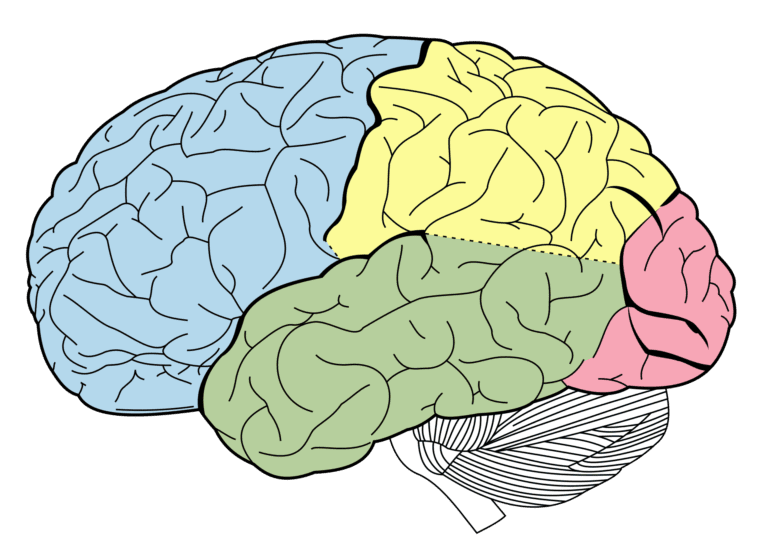

To understand the benefits of writing for the mind, I’d like to introduce you to some basic concepts of language processing in the brain. Language practices include listening and talking as well as reading and writing. Listening and reading are receptive processes while speaking and writing are generative processes. Over time we have learned that each of these 4 languaging processes require a complex coordination of all 4 lobes of the brain.

The frontal lobe (in blue above) is the home of executive function (judgement, movement, problem solving). The parietal lobe (in yellow above) recognizes and interprets multiple modes of meaning making (verbal, visual, aural, gestural, and spatial). The occipital lobe (in red above) is where vision processing takes place. The temporal lobe (in green above) is responsible for memory, processing language, and emotional regulation.

Writing to Learn

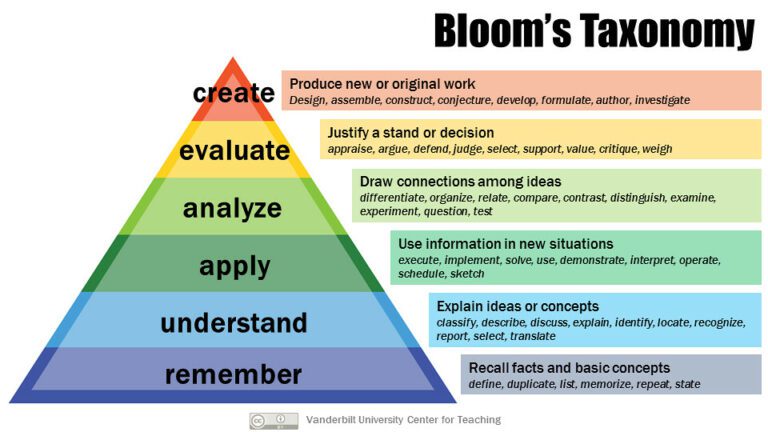

In 1979, a middle school writing teacher by the name of Janet Emig embarked on what would become one of the most well-known research studies in the field of writing studies. She referred to writing as “a uniquely powerful multi-representational mode” and was one of the first teachers of writing to interrogate writing from a cognitive lens. Prior to her work, most people considered writing to be a container for expression—a vessel carrying the intended meaning from sender to the receiver. After Emig’s work, the way we teach writing at the college level was changed forever; we began teaching students to think about not just what they write but how they write and who they are as writers. Teaching writing (content and products) was reframed as teaching writers (behaviors and reflections). If you look up Bloom’s Taxonomy you will see that remembering is essential for learning. You will also see that the most complex cognitive function a learner can engage in is creativity. From remembering to creating, writing is essential for learning.

Part III: Physiological Benefits of Writing

Have you ever felt like your mind was so filled with ideas that you were almost compelled to put them into writing just to sort them out? If you feel like this now, try a practice we use often in the writing class: freewriting. Freewriting is a stream-of-consciousness practice that encourages idea generation and writing production free of editing or censorship. Outside of the classroom some people might call this “venting” or “getting it out” as a way of gathering all of their ideas in one place. In this context, the product is not the goal. We’ve all heard the adage “It’s the journey, not the destination,” or maybe you’re familiar with the Flannery O’Connor quote “I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.” Both of these concepts support the theory that writing is a productive languaging process that is deeply personal and incredibly engaging for the mind. Returning to Emig’s work, she built on the work of Jerome Bruner and Lev Vygotsky to conclude that writing is a mode of learning in that it is enactive (“by doing,” involves the hand); iconic (“by depiction in an image,” involves the eye); and representational or symbolic (“by restatement in words,” involves the brain). Writing becomes an embodied process—which we will explore further in Part III: Physiological Benefits of Writing. For now, it suffices to say that because of how the brain is wired writing engages the prefrontal cortex at the same time as it is activating our language faculties, at the same time it is requiring fine motor skills through handwriting or typing, and so forth; the brains processes overlap and converge, flowing from one into another. Putting thoughts into words on paper or on a screen naturally leads to other brain processes: finding patterns, experiencing emotion, identifying problems, generating solutions, visually scanning for typos, etc. The brain is designed to learn and writing gives our brains a means of focusing—which also helps improve recall later on.

Writing to Remember

Understanding how the brain works to generate speaking and writing can help us understand why we tend to remember something if we’ve written it down. Consider this: you have a list of 5 items you need to grab at the grocery store and you’re worried you’ll forget them so you write them down. At the end of the work day, you walk into the store and realize you’ve left the list at home. But, you are still able to remember all 5 items. Why?

The human memory is complex brain function, and there is much we do not know. But here is what we do know in terms of what helps us to remember things:

- focused attention (without mind wandering)

- visualization (an image connected to a concept)

- activating prior learning (relate this new idea to something you know already)

- sequencing or organization (find a pattern or order to the ideas)

Now, if we return to the grocery list example, all four of these memory “best practices” were met: writing requires focused attention because it is simultaneously iconic (visual), enactive (embodied), and symbolic (language). Writing is visual not only because we must inscribe shapes called letters onto the surface of paper, but also because we quite naturally imagine the grocery list item as we write it. Or we might recall to memory the space in the store where that item is usually found (activating prior knowledge). In that visualization of the store, we might imagine the route we will take through the store to visit each section—thus finding a sequence in which we might pick up those items. And to think: all of this processing occurs in the brain as you write 5 words on a sticky note.

Now, the benefits here go beyond remembering your grocery list. Improved long-term memory is associated with a higher quality of life overall. And, activities that keep the mind active have been shown to keep the brain adaptable into late life aging.

In our next post Part II: Emotional Benefits of Writing, we will explore specific uses of writing in therapeutic contexts as well as prompts you can use on your own to work through some common emotional hurdles.