Previously, we dove deep into the cognitive benefits of writing. Now, we shift our focus within the human brain to the space of emotion. There are countless therapeutic interventions that explore emotions and utilize writing, but none quite to the extent of Narrative Therapy. The underlying assumption of Narrative Therapy is that language not only describes our world, it creates our reality. Language is the source of hurt; thus, language is the source of healing.

Here’s an example of how we use language to talk about physical vs. mental illnesses that helps create the reality of those who experience them. A few years ago I broke my foot, but even while healing, never did I describe myself as “broken.” Something outside of me caused my foot to break. It is not internal to me therefore I do not identify with it. Many people who manage a mental illness identify with their illness in a way that differs from physical ailment. For example, if I am feeling down, I might call myself “depressed.” Describing myself as being in a state of depression, rather than expressing my emotion of feeling hopeless, is called internalizing and it can worsen over time until I start confusing myself (who I am) with my depression (how I am feeling).

Unfortunately, our understanding of physical illness vs. mental illness remains worlds apart and it’s evident in how we speak about it. You would never tell someone with a broken foot to forego professional help and just “try getting out more.” We would be offended if someone accused us of manifesting cancer in the way others suggest mental illness is a choice. This is just one example of how the language we use creates our reality.

The sections below explore different approaches to writing that offer emotional benefit. The first and the last are taken directly from Narrative Therapy, but the others are simply best practices I have either observed or utilized along my journey.

Externalization: Get it Out

Since writing requires the use of language, there are many ways in which writing can help shift our reality in helpful and healthy ways. Given the example above, the way to reverse internalizing is to externalize a problem. Narrative therapists do not believe that problems originate or even dwell within an individual. Instead, they intervene therapeutically through an individual’s relationship with the problem. And they use writing as one way to externalize said problem. For example, I ask you to consider something that is giving you trouble in your life (e.g. stress, depression, money). Now, sit down and write a letter to that problem:

- “Dear Stress, I really wish I could manage you better.”

- “Dear Depression, My life was happier before you showed up.”

- “Dear Money, You do not control me. You are a tool I can use to achieve my goals.”

Target your emotions and complaints at the problem itself instead of at yourself. Tell your problem what it is doing to you. Demand it stops. Or negotiate. Compromise. Write whatever you feel like writing to this problem. Using the letter format, you can speak directly to your problem with the added benefit of firmly situating your problem outside of yourself.

Identify Emotions without Identifying with Emotions

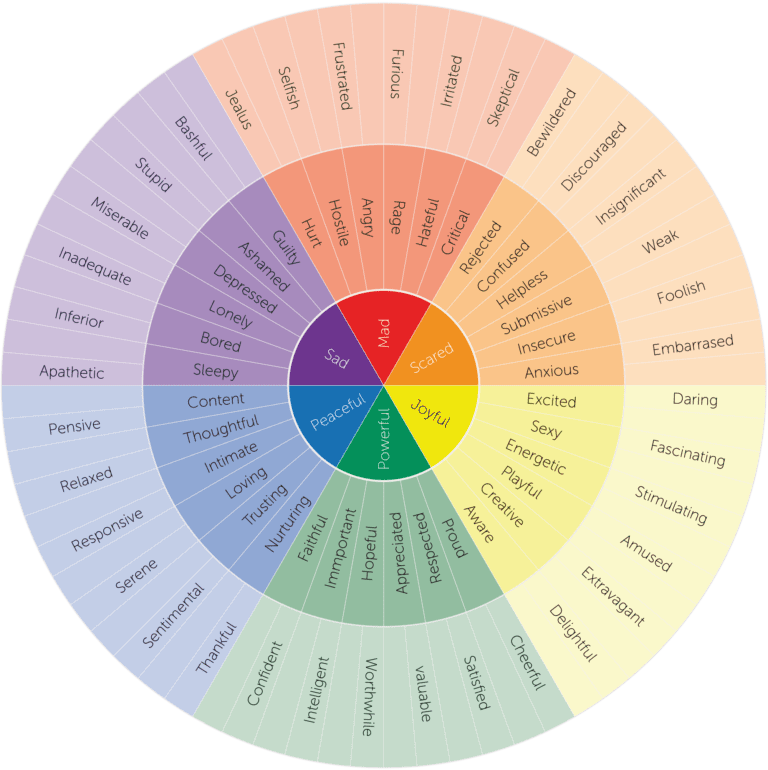

One aspect of our culture I often criticize is the absence of emotional intelligence in the way we raise our children. Newer methods in child development are beginning to offer emotional identification (especially during the toddler ages). But overall, we aren’t great at identifying how we feel. In fact, English has significantly fewer vocabulary terms for feelings when compared to other modern languages. Writing out our emotions forces us to choose a word to describe how we are feeling.

There is a very simple prompt that offers the opportunity to identify an emotion and explain its cause. I challenge you to complete this prompt at least 5 times in one sitting.

“I feel _____ because ______.”

As emotions come, write each one down and try to uncover the cause. Identifying multiple emotions at one time provides concrete evidence that our emotions are constantly changing, rarely 100% rational, and never permanent. Feelings are fleeting and they are not facts. The exception to this is in the case of traumatic stressors in our life that remain with us until we can find a healthy way to process them.

One way of beginning to heal our hurts is by putting them into words. Acknowledgment is powerful. For people who have been managing post-traumatic stress, this alone can be a difficult task, and should be done while in the care of a mental health professional.

I was hurt by __[person]__ because __[person’s actions]__. It made me feel __[emotion]__.

Right now, I am safe. I feel__[emotion]__ while writing about it.

I didn’t deserve __[hurt]__.

Often we retain childhood hurts because at the time of the event, we were too little to comprehend or communicate our emotions. So, for this prompt, I might recall a particularly troubling bully from 2nd grade: “I was hurt by Kristin because she called me ‘fat’ at soccer practice and all of the girls laughed. It made me feel embarrassed and shameful. Right now, I am safe. I feel angry while writing about it. I didn’t deserve to be the target of her bullying.”

Digging Deeper into the Purpose of Emotions

Every emotion we experience, pleasant or unpleasant, serves a purpose. This prompt invites you to write down the emotion and identify the ways in which it serves you. What role is that emotion playing in your life right now? The emotion may be helpful at the time, but chances are that there are other, healthier ways to meet that need. After identifying 2-3 emotions and the needs they serve, consider alternative ways to meet those needs.

- Frustration reminds me that I’m not in control and that’s uncomfortable. Before I get to the point of frustration, I can approach tasks with a fresh mind and schedule plenty of time to complete them.

- Anger alerts me to something unjust. Instead of getting angry, I can allow myself to feel the emotions that lie beneath anger: pain, fear, sadness.

- Jealousy identifies unknown desires of mine. Rather than comparing myself/my life to others’, I can live intentionally and work to understand what I need and want in my life.

- Depression gives me permission to hide from the world. Speaking kindly to myself and giving myself permission to rest when I need to is a healthier way to restore when I feel depleted.

Tell me a Story

A fascinating phenomenon of the human brain is enacted when we tell stories. For most of human history, oral storytelling was the primary means of a culture’s most important events, people, and values. And there is a reason why the form of storytelling is so effective for us: mirror neurons help us identify with the emotional elements and experience escape. It is now understood that when we are being told stories, our brains access the related areas for us to come as close to experiencing the story as possible. For example, a story that takes place in a bakery will activate our sensory cortex and the sense of smell. An action-packed movie can activate our motor cortex, causing us to tense our muscles in response to that high-speed car chase. While we know that the story is distinct from our current reality, the brain works very hard to blur the lines.

Understanding the power of the brain to create worlds into which we can escape, we can utilize writing to literally revise and retell stories of our lives.

- Retell a story from a new perspective: reimagine the events, the people, your place in the story, etc. Make it so real that you see yourself differently afterwards.

- Example: When I was young, I was diagnosed with ADHD and it made me feel insecure and dejected. I could rewrite that story through the lens of a superhero who is discovering her powers of hyperfocus, emotion detection, and social intelligence. I can hear the campy music now!

- Retell an experience with another person (someone other than yourself) as the main character. Writing from a space of compassion, consider: what was that event/time like for them?

- Example: Because I was young when it happened, I had only ever considered my experience of my mom’s bariatric surgery and hospitalization. I could take her point of view and retell certain events through her eyes to start developing some compassion and empathy for what she went through.

These four approaches to writing about/for emotion are the tip of the iceberg. There are countless more if you are so inclined to explore. Externalization, identifying emotions, and crafting alternative stories of self are just some of the benefits of expressing our emotions in the written word.

In our next post Part III: Stress-Reduction Benefits of Writing, we will recall what we know about the body’s stress response and explore how writing can help us to manage stressors in ways backed by the latest research.